Earlier this month, 1990s Northwest punk-pop darlings Hazel climbed onto the main stage at Macefield Music Festival for what one assumed would be a hotly anticipated reunion show... only to be greeted by around 20 audience members. Granted, it was outdoors in nasty weather, and the crowd doubled in size before it was all over, but the setting called for hundreds of people, not dozens.

At this fall's inaugural edition of Chance of Rain Urban Arts and Music Festival, which was attempting to fill the void left by Decibel Festival's hiatus, attendance was similarly underwhelming for bills consisting of strong techno and industrial-electronic artists at the Re-bar and Crocodile showcases that I attended.

The Fete Music Festival—which was to feature Nas, Rae Sremmurd, and other prominent hiphop figures at White River Amphitheatre—was canceled due to low ticket sales.

Several other smaller niche fests reported dwindling attendance figures this year, but the problem extends to the big events, too. Back in 2014, the huge outdoor extravaganza Sasquatch!, which happens annually on Memorial Day weekend, had to eliminate its second Fourth of July weekend dates due to poor sales. Plus, ticket sales for the 2016 edition dropped by 50 percent to 11,000, according to the Oregonian, for which some blamed a less stellar lineup and a weaker Canadian dollar. And looming on the horizon, Paul Allen's Upstream Music Fest + Summit threatens to wipe out the competition next spring, as it takes over CenturyLink Field and Pioneer Square. What can a beleaguered festival organizer do in such an oversaturated market? Is the Northwest suffering from festival glut?

STILL ROOM FOR GROWTH?

I spoke to a dozen people who put on music festivals in the Seattle area, and one thing I learned is, the bigger the event, the more its operatives speak in glittering generalities that seek to conjure warm and fuzzy feelings. The other conclusion: Bigger fests with more corporate sponsors tend to be doing better than smaller, more-DIY fests.

Rob Thomas of AEG Live, which took over the massive annual cultural smorgasbord that is Bumbershoot in 2015, said: "Attendance has been increasing along with the excitement and positive feedback. There are many variables that go into a successful festival. Success for us is hearing about the amazing memories and new friendships that have been created at Bumbershoot."

Thomas welcomes competition because it "pushes everybody to work harder to provide a better festival. One of the best festival experiences I had this year was at the Northwest Tea Festival. It was the ninth year for a fun and educational two-day event showcasing the multifaceted world of tea. I truly hope the festivals in Seattle will continue for many more years."

Adam Zacks, Sasquatch! founder and senior director of programming for Seattle Theatre Group, isn't ready to declare peak festival, either: "With the population growth in our region, we may or may not be there yet. If we look at other markets, Chicago being the most extreme example, there is still room for growth. It's not easy, though, and there is certainly plenty of risk in any new venture like this. I think it's forcing us all to be more creative, thoughtful, and patron-centric."

Eli Anderson, who books Capitol Hill Block Party, which drew about 20,000 attendees for each of its three days, admits that Seattle hosts an excess of fests and events every weekend. "I think there's a certain brand of mega-festival format that is really transparent and dull. People don't want to be led out into a field and shown a series of logos and be told that it's fun. That's the sort of thing people are going to get burned out on and reject. While Block Party is still a large-scale event, the setting and relative size help keep us more interesting than all that."

TOO MANY OPTIONS

While large music festivals have thrived in Europe at least since the mid 1980s, they've burgeoned only relatively recently in America. Some industry pundits attribute this to millennials' desire for communal experiences and their love of sharing said good times via social media. Consequently, fest organizers compete fiercely to give patrons the most interesting, multifaceted experiences possible. Another thing spurring big festivals: Their corporate sponsorships—in exchange for branding privileges—enable them to pay higher rates to artists than they can earn at conventional club gigs.

In conjunction with that development, several smaller festivals have sprouted in recent years to capitalize on the resurgent interest in psych rock and garage rock, like Seagaze, Pizza Fest, and the defunct Hypnotikon. Other promoters try to tap into hardcore aficionados' zeal for electronic, experimental, jazz, and heavy metal. If there's a niche genre, the thought goes, there must be a festival to celebrate it. Decibel is an example of a scrappy little fest that blossomed into a worldwide phenomenon. That, however, is the exception. Most niche fests fizzle quickly or operate on a humble, low-profile scale.

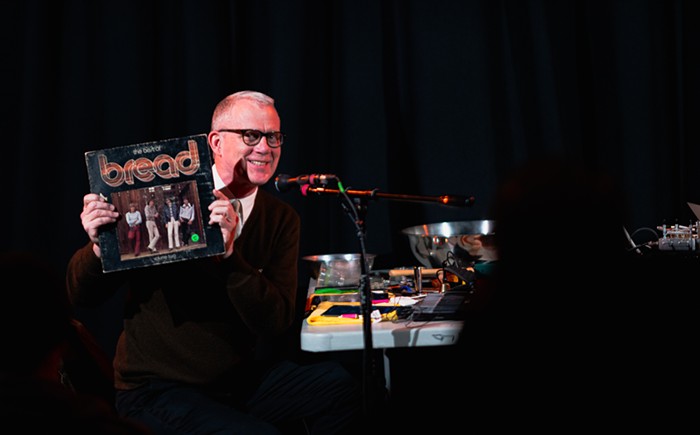

Leigh Bezezekoff and Michael Stephens of the Ballard-based Macefield Festival note that people may be over the concept of expensive large festivals with very similar bills. They point to their schedule of Hazel, Reigning Sound, Psychic TV, the Sonics, Jesse Sykes, and Mark Lanegan as deviations from the norm. "Our festival attracts true music fans, not those just looking for a festival experience," Bezezekoff said. "I think as long as we continue to do that, we'll be okay." Stephens adds, "We are really trying to establish ourselves as a festival for those that maybe aren't that into festivals. We know who we are and why we are doing this, but it is hard work." Macefield's bosses claim they exceeded last year's total for presales, but the poor weather seriously hurt their walk-up numbers. They're reconsidering the concept of holding outdoor sets in October.

The electronic-music-oriented Chance of Rain also cited attendance shortfalls. Lack of sponsorship and late lineup announcements hobbled promotional efforts, according to organizers Michael Manahan and Alison Pugh. However, Manahan posits that Chance of Rain can offer a respite from festivals' homogeneity and predictability. He wants his event to embrace the city's social, cultural, and geographic diversity. "We believe the electronic music and urban arts communities of Seattle still remain underrepresented by many of the festivals that call Seattle home," he said. Pugh said it's increasingly important for CoR to differentiate itself from the pack. "It's not just about the big names; most of my favorite moments stem from encountering the unexpected, which, frankly, never has big names involved."

Pizza Fest head Pete Capponi blames low numbers at this year's PF on there being too many high-profile events—including Doe Bay Fest and Pickathon—happening during the same weekend (August 4–6). He adds, "I think people get a little burned out on having to pack so much into the limited number of summer weekends when there is actually good weather. But, ultimately, I think it's a good thing to have so much [going on]."

MORONIC CHILDREN WITH NEON SUNGLASSES

Founder of the annual experimental-music blast known as Debacle Fest, Sam Melancon feels that Seattle suffers from a surfeit of themed programming. "Every show, art opening, DJ night, and record fair has moved into this model that everything happening in a given month has to be a multimedia social EVENT. Just being a show or an opening isn't good enough anymore to get people psyched to come enjoy. I think the level of quality of what is actually on offer could be so low that people are papering over with 'concepts' and half-assed themes, because it is exciting to say you have a festival, event, monthly series.

"It's easy to write up a document of what a night is supposed to evoke in patrons; it's much harder to actually see it through and put the work in that creates a venue for phenomenal and consistent art to be produced." Debacle "barely met expectations" for attendance according to Melancon, but for a fest that spotlights obscure, challenging artists, it did respectable numbers. "We try not to hang our entire budget on a single 'big name' and let smaller artists shine through."

One newish event that seems to be doing fine on its own terms is Northwest Psych Fest, held at the Sunset Tavern and Conor Byrne Pub. Leaders Peter Koslik and Nick Arthur judge success not by ticket sales but by the quality of showgoers' experiences. As Arthur put it: "People fell in love. Bands became best friends. Bands broke up. We left people in joyous tears, and we pissed people off. We lost tons of money." Both men decry what they perceive as cronyism within Seattle music fests—too many events where friends' friends' bands get booked regardless of merit. "At best," said Arthur, "you get an expensive, high-speed, three-day marathon of what anyone could get parsed out over any month—or at worst, you get a frightfully expensive event filled with moronic children with neon sunglasses thinking Ecstasy is enlightening, listening to music that should have been washed away in the '90s."

Koslik said that one of Northwest Psych Fest's top priorities is to "support lesser-known but talented musicians who are struggling to survive in a city that seems hell-bent on driving them out. To that end, I believe we have achieved something, even if it's just a spark of light in the darkness."

Both organizers see a proliferation of events emphasizing "psychedelic" music, but observe an attendant false advertising. (Lo-Fi's Seagaze, Royal Room's Psychedelic Festival, and Neumos' Psychedelic Holiday Freak Out are recent examples, though one could argue they did possess genuine psychedelic content.) "You can't fake your way through an acid trip, and you can't fake your way through a psych fest and expect people to have a profound experience," Koslik asserts. "More than a few people have told me that Northwest Psych Fest was the best concert experience they have ever had. When I ask them why, they often have no answer. They just get it. To me, that means something and that's why we'll keep going."

WHAT IF WE GIVE IT AWAY?

Veteran Seattle guitarist Dennis Rea (Moraine and many other bands) has spearheaded progressive-music fest Seaprog since 2013, but he took a hiatus this year due to its organizers' musical commitments. Festivals run by musicians (e.g., Rafael Anton Irisarri's late, great Substrata) typically treat artists well and induce a strong camaraderie among both performers and audiences. That's been Rea's MO. Even if they've lost money every year, Seaprog has been satisfying to Rea for its "truly memorable performances and helping to foster a sense of community among players and enthusiasts of the sort of music we showcase." He also lauds the festival format for "building bridges between previously isolated factions of musicians and sparking a number of musical collaborations that likely wouldn't have come about otherwise."

Sadly, Seaprog has had to move the date of its 2017 event at Columbia City Theater because it fell on the same weekend as Upstream. Rea, too, acknowledges festival saturation. "We're finding it increasingly difficult to find a weekend on the calendar that isn't already crowded with a plethora of competing happenings," he said. "The recent proliferation of festivals also hinders any efforts we might undertake to obtain a modicum of public funding, as we'd be up against daunting competition. However, among our native constituency, which includes a good number of older listeners, we've found that they're reliably more likely to attend a festival with multiple acts and a sense of community camaraderie than the usual weeknight gigs in dive bars to which Seaprog artists are typically relegated—that alone makes it a worthwhile endeavor."

One model worth exploring is the free festival. That's the route Luis Rodriguez has taken for six years with Block Party at the Station, held near the Beacon Hill coffee shop/hiphop stronghold. Rodriguez's annual goal is to draw people of color and LGBTQ folks to his event in a city that's about 70 percent white, and he achieves it. "It was considered by many people in Seattle to be the most POC party in town," he said. "We brought amazing artists that anywhere else you'd have to pay for."

That being said, Rodriguez has ambitions to lock in sponsors and donors—but no corporations, thank you—to the Block Party, so he can pay his artists with something more than coffee. He takes pride in his event showcasing local hiphop artists who rarely appear at other fests. A staunch advocate for people of color and a champion of the defunct Black Weirdo parties, Rodriguez also hopes to bring the Afropunk Festival to Seattle, with a team helmed by fellow local people of color. So far, Afropunk has happened only in Brooklyn, Paris, and Atlanta. It would be a tremendous coup, for sure. However, he said, "it will be very difficult to make that happen in a very white city."

As it stands, if you want to succeed financially as a festival organizer, you need to either have deep pockets, or tap into a demographic/genre niche that's been underserved and is hungry for high-quality bills, or present innovative entertainment concepts that aren't too esoteric. All of this is much easier said than done. It may be time to realize that too many music-festival organizers have overestimated the region's appetite for their entertainment concepts. Seattle's population keeps growing, housing costs keep rising, and people can commit to only so many multiday extravaganzas per year.