Beloved travel writer and novelist Jonathan Raban died yesterday, on January 17. He was 80 years old.

Raban was born in Norfolk, England, but if you ask any Pacific Northwest fan they'd likely tell you he was an honorary local. He had called Seattle home since 1990 and won both the Pacific Northwest Booksellers’ Award and the Governor’s Award of the State of Washington in 1997. To many of us here at The Stranger, he was a genius. Literally. The Stranger awarded Raban a Genius Award in literature in 2006.

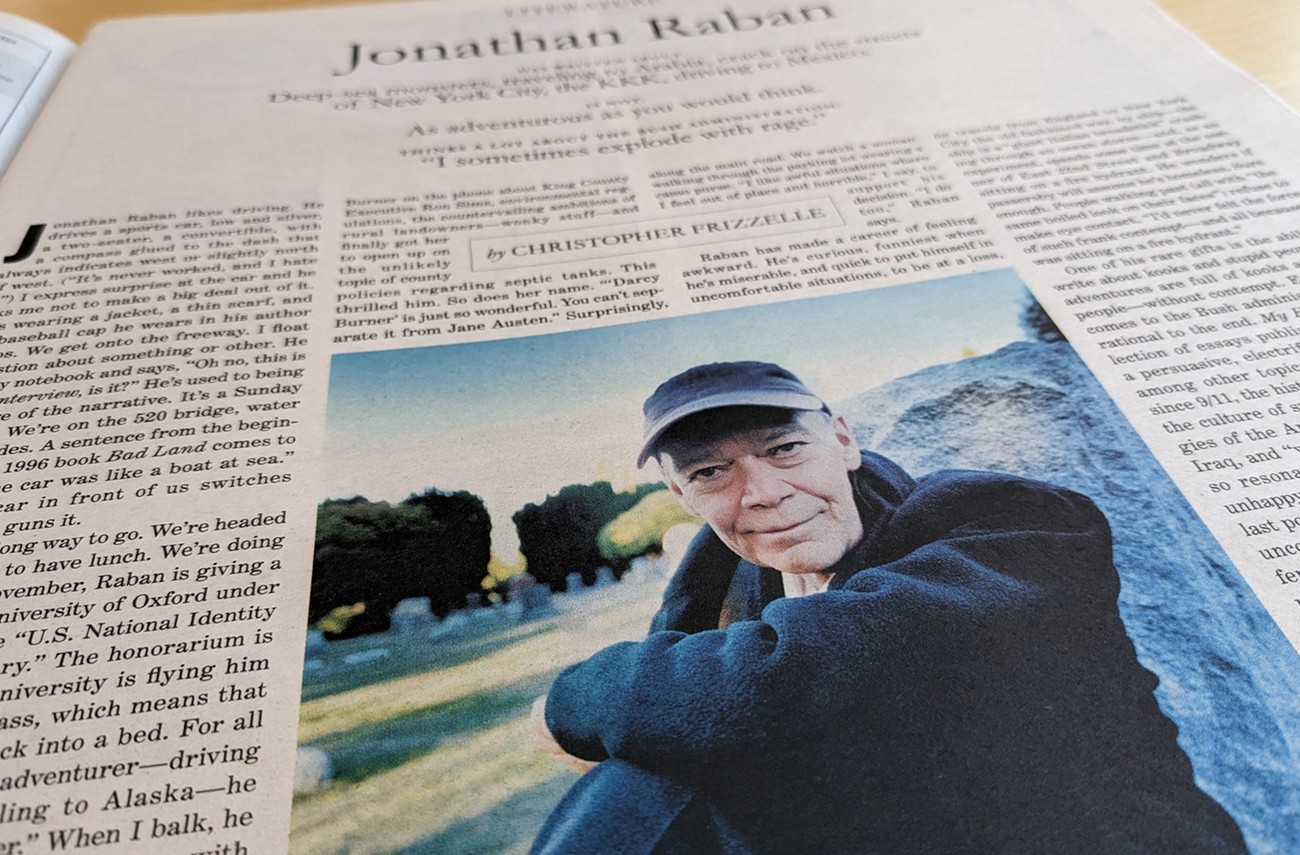

That year, former Stranger editor Christopher Frizzelle profiled Raban for the October 19 issue. The two drove to North Bend to have lunch because of course a profile on Raban would involve a long car ride. In that piece, I learned that Raban, who I'd only ever known as an esteemed and beloved travel writer, did not consider himself a travel writer at all.

Frizzelle writes:

For all his reputation as an adventurer—driving across America, sailing to Alaska—he says he's 'not a traveler.' When I balk, he says, "Most enterprising Americans with cheap miles on their cars would beat me hands down. It's just that all the travels I've done I've written about."

Frizzelle also perfectly captured one aspect of Raban's writing that made it so readable, so smart: rationality. He writes:

One of his rare gifts is the ability to write about kooks and stupid people—his adventures are full of kooks and stupid people—without contempt. Even when it comes to the Bush administration, he is rational to the end. My Holy War, a collection of essays published last year, is a persuasive, electrifying dissection of, among other topics, American politics since 9/11, the history of the Middle East, the culture of surveillance, the mythologies of the American West, the mess in Iraq, and 'why the call to jihad answers so resonantly the yearnings of clever, unhappy, well-heeled young men.' On this last point, Raban writes brilliantly on the uncomfortable similarities between the fervor of his adolescent atheism and the religiosity of John Walker and the young members of the Taliban.

The Stranger was lucky enough to print some of Raban's original work, too. In 2005 he wrote an essay about the London train bombings. Later on, he wrote features on President Barack Obama's winning political strategy and on authoritarianism in America. More recently, in 2017 he wrote a brilliant analysis comparing his father's experience in World War II to the evacuation event at the center of Christopher Nolan's Dunkirk:

The question is this: How do you present Hell on earth, Hell in the air, and Hell at sea on celluloid? For Christopher Nolan, much of the answer is do it in ultra-high-definition 70 mm IMAX film and show it in IMAX cinemas, which he has done before with movies like the Dark Knight films and Interstellar, repeatedly arguing the case for restoring the "theatrical experience" to moviegoing. Dunkirk is meant to be a nonstop 114 minutes of unalleviated spectacle, a massive collage of beautifully composed pictures, each one lasting for only a few seconds, of gunfire, flames, drowned corpses, exploding bombs, aerial dogfights with numerous plane crashes, and more, much more. The soundtrack includes a constant ticking noise, which might be the sound of a palpitating heart or that of a clock registering the suspense of passing time. The film's cast is British-stellar, with two theatrical knights (Sir Kenneth Branagh and Sir Mark Rylance) and, for good measure, a teen heartthrob rock star, Harry Styles (sans his famous hair). It also has a PG-13 rating, which tells us something important about the nature of this sensational action movie.

Nolan is now one of the greatest and most inventive movie technicians. He also lists the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges near the top of the people who influenced him, which signals his taste for cerebration, and can be seen in some of his earlier movies, like Memento and Insomnia. But the most Borgesian quality in Nolan's work is his cool detachment from the world he describes. Dunkirk shows a world full of terror, but Nolan goes to great lengths to ensure that his audience is never terrified. We sit in our seats munching popcorn and watch other people undergoing terrifying experiences.

Raban is survived by his daughter, Julia. His memoir, Father and Son, is scheduled to be released September 23.

Rest in peace.