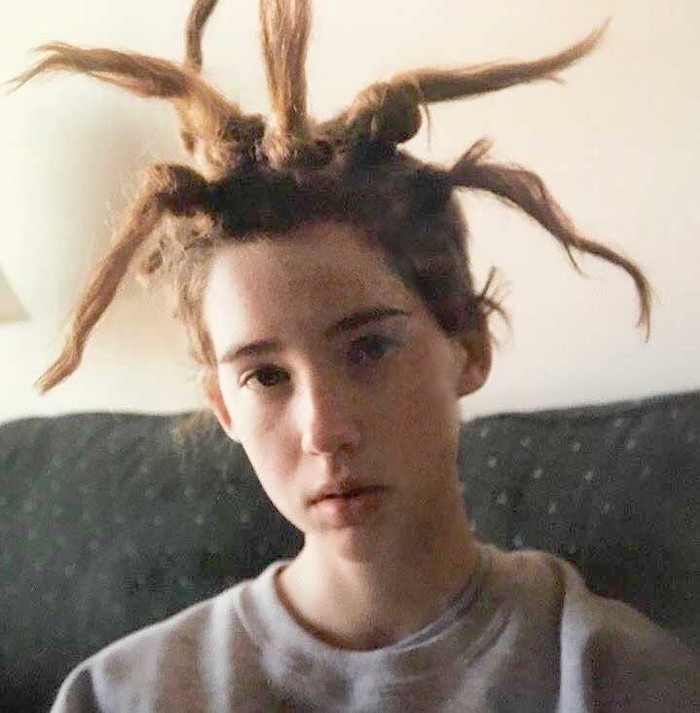

I, Katie Ronan Herzog, was once a white girl with dreadlocks.

I know. I know. It's bad. My only defense is that I was 15 years old and under the impression that Ani DiFranco was a style icon. This was 1996, and while the term "cultural appropriation" may have already entered the lexicon at, say, Oberlin College, I didn't live in Oberlin. I lived in rural North Carolina, and I was trying very hard to distinguish myself from all the poufy-banged preps (known today as "basic bitches") who ruled my school.

It is not easy for a fine-haired Caucasian such as myself to grow dreadlocks, and because this was before the internet, I made it up. I twisted my hair around my fingers into little ringlets and then teased them beyond repair. My friends pitched in: standing behind me in the cafeteria, twisting and teasing my hair. It was almost a community project.

It didn't really work: The "dreads" fell apart as soon as I got in the shower each night. So I added wood glue to the mix, which someone (a liar) told me would work. I wish I could say I was kidding. But, alas, if you ever want to know what wood glue does to human hair, check out my sophomore yearbook.

Eventually, after much teasing, as well as adding various other household products to my hair, I did, in fact, succeed: I had dreadlocks (kinda). I then proceeded to make the look even stranger by tying them in knots. It was as if Coolio had been reincarnated as a 15-year-old white girl in rural Appalachia.

As ugly as this look was—and it was truly hideous on me, although when people, my family included, informed me of this obvious fact, I was sure they just didn't get it—it served a purpose. Like a lot of teenagers, I was desperate to stand out in the monoculture in which I grew up. Needless to say, the dreadlocks worked, especially combined with my uniform of steel-toed Doc Martens, a dozen hemp necklaces, and jeans with legs as wide as a VW wagon. Everyone knew who I was: the girl who looked like a freak.

I now see that there were better ways to distinguish myself as different, special, one-of-a-kind. I could have come out of the closet, for instance, which really would have shocked people. But this was the '90s. Too dangerous. It was much easier to put wood glue in my hair and hope no one noticed I was a dyke.

This worked for a while. Aside from the Marilyn Manson–listening goth kids, I was the biggest weirdo in my school. At least until a girl a year older came back from a trip to Amsterdam with beautiful blonde dreadlocks she'd paid a professional stylist for. I was appalled that she'd taken the easy way out. (Paying for dreadlocks? What kind of monster did that?) But hers, unlike mine, actually looked pretty good, and I cut mine off the very next day.

There is little remaining evidence of this time in my life (thank god). But a year ago, my girlfriend found the photo of me shown above, and she commissioned an artist to illustrate it. I came home from work to find two dozen copies of the artist's drawing hanging in our bedroom. There are some things—be it bad fashion or gayness or just who we are—that you can never escape, no matter how hard you try to forget them.