Most people accept by now that the climate is changing and it's a direct result of carbon emissions. Politicians, NGOs, academics, the media, and activists spend time, energy, and money thinking about how best to get the world off of fossil fuels, and they do it while facing resistance from the fossil-fuel industry and the federal government.

But there's an equally serious problem aside from achieving carbon neutrality in the future: What the hell are we going to do about all the carbon we've been emitting since the dawn of the industrial revolution?

That's the problem Paul Gambill is trying to solve.

For those who knew him as a kid, it's probably a surprising turn of events. Gambill was raised in a conservative, Catholic, Fox News–watching family in Phoenix. He was the (rare) type of teenager who cried when Ronald Reagan died. He knew the climate was changing, but he didn't think human emissions were a significant cause of it. Gambill, now 31, might have continued to hold this belief, but then, at a music festival after college, something happened to change his life.

And it happened, as these things tend to, while on magic mushrooms.

"I was at a music festival in Michigan, and I remember sitting on the lawn while some band was playing," Gambill tells me at his office in Ballard. "I was watching this tree that had coin-shaped leaves fluttering back and forth like sequins in the wind, and I was just enraptured by that. I'd never felt more connection to nature at any point in my life, and it completely changed how I related to the world. I came away from that with a love for the natural world and an understanding that we are a part of everything else on earth."

The revelation stuck with him. But despite his shroom-induced epiphany (and his love of the band Phish), Gambill isn't exactly what you'd call a hippie: Over the years, his politics have evolved, and he's now one of a small but growing number of libertarians working to combat climate change and its impacts.

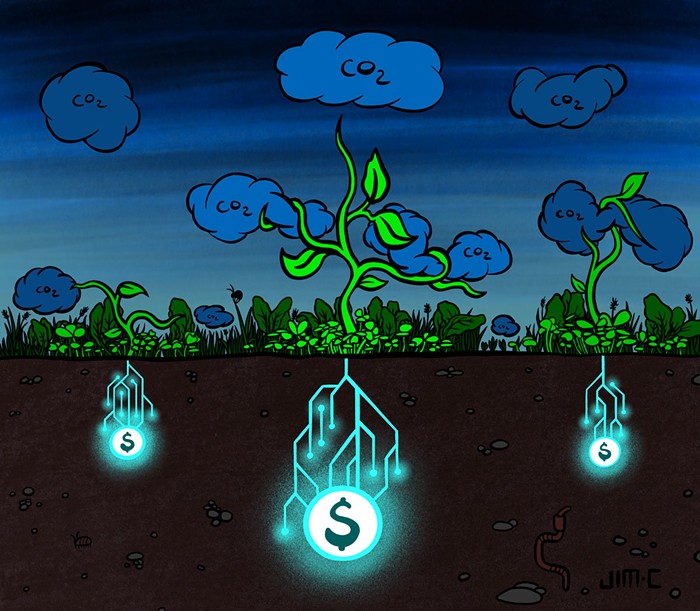

What Nori, the company Gambill founded in 2017, does is both very high tech and very old-school. They've created a marketplace that connects governments, corporations, or individual people with farmers who agree to transition from conventional industrial agriculture to regenerative farming.

The farmers, in essence, revert to the way people farmed before the advent of industrial machinery. They don't till or use fertilizers, which in the long-term damages soil along with water quality. Instead, they use compost, mulching, and cover crops that regenerate the soil itself—and, in the process, remove carbon from the air and sequester it into the land.

Regenerative farming is labor-intensive and expensive to adopt, and it decreases yields in the short-term. But long-term, it can increase yields, improve the health of the land and the water, and remove carbon from the atmosphere at the rate of about one ton per acre a year.

Marketplaces where individuals or institutions can buy or sell sequestered carbon already exist. You can also purchase carbon offsets—which are basically promises to reduce emissions—from some airlines, car companies, and retailers. But this practice has long been plagued with problems, in part because offsets are poorly regulated and easy to manipulate. Multiple investigations over the last decade have found that, often, little of the money being exchanged actually goes to reducing carbon. Instead, it goes to the middlemen who buy and trade carbon offsets on secondary markets. And that's not the only problem. It's notoriously difficult to verify that these offsets are genuine, and the same ones tend to get marked up and sold over and over again.

And then there's the potential for fraud. In 2018, for instance, 12 people were tried in France for tax fraud and money laundering through a carbon-trading scheme that prosecutors claim cost the European Union five billion euros. French authorities called it the "heist of the century."

Nori does things differently. Instead of reducing future emissions, they work with their partners—usually farmers, although they hope to move into forestry and ranching—to remove carbon that's already been emitted. Once that carbon has been removed, the company works with a third party to verify it. They then issue a certificate to the farmer, who sells it to a buyer for NORI tokens, the company's form of cryptocurrency. After it's sold, the carbon removal is recorded on the blockchain and retired immediately, so it can't be sold on secondary markets. It's like bitcoin, but for a good cause.

Gambill says that when he approaches farmers, it's not climate change he talks about, but money. The farmers on Nori's marketplace receive 90 percent of the price of the sale. In similar programs, Gambill says, that number is more like 10 percent.

The other selling point, Gambill says, is the impact of regenerative farming on the soil. "Topsoil is eroding. It's getting harder and harder to get the same yields. The farmers recognize that we have to transition to regenerative agriculture or we won't have food in the future." And this way, they get paid to do it.

Gambill doesn't just tailor his message to farmers. He tailors it to everyone he speaks to. When he speaks to chief financial officers, he talks bottom line; when he speaks to environmentalists, he talks about sustainability; when he speaks to conservatives, he talks about national security and self-defense. And he's got a knack for reaching across party lines. Unlike most people working in this field, he understands climate-change skeptics—because he used to be one.

"Carbon is not evil or immoral," he says. "It's just in the wrong place. People shouldn't feel shame about using energy. Fossil fuels have lifted billions of people out of poverty and prevented countless famines. But there's a consequence to this, and people respond better to incentives than they do to shaming. I want them to see there's a positive action they can take that has real results."

Still, carbon removal will not solve all our problems. Gambill says that all US croplands could sequester about a billion tons of carbon a year. Reforestation, kelp farming, and emerging technologies can do more, but it's still a drop in the rapidly rising ocean compared to the 40 billion tons of carbon the world emits every year. That's where Gambill's libertarian values come slightly into conflict with the reality of the situation, because he knows that the free market can't stop polluters from polluting. That's going to take government intervention.

"We should treat carbon the exact same way we treated leaded gasoline and getting CFCs out of refrigerants to fix the ozone hole," he says. "Say anyone who produces a product that puts carbon in the air would have to reduce the carbon content every year until it gets to zero. It's not about the government picking market solutions, it's about saying, 'You have to meet these objectives, and I don't care how to you do it.'"

But for the other part of this—bringing down to earth the carbon we've already emitted—Gambill hopes Nori can be part of the solution. "For a long time, people were really reluctant to talk about carbon removal because they were concerned it would give emitters a pass and they wouldn't decarbonize," Gambill says. "And there is some truth to that, for sure. But we don't have a choice anymore. It's too late to just focus on reducing emissions. We have to do something else."