I’m writing from Monroe Correctional Complex about an hour north of Seattle. I want to talk to you about a bill currently making its way through the Legislature that is near and dear to my heart: House Bill 1324, otherwise known as the Fresh Start for Criminalized Youth bill.

This bill would end the use of juvenile “points” in the adult sentencing system and allow those of us whose childhood crimes lengthened our sentences to ask to shorten them.

I’m 36. Since the age of 14, I’ve only spent about 15 months in the “free world.” I got my first-strike offense under our three-strikes law at the age of 17 after spending my life bouncing around relatives’ homes and juvenile detention. I had little choice in where I went or who I lived with because at the age of four my father stabbed my mother to death in front of me. I experienced abuse at the hands of my caregivers both in and out of juvenile detention. I got another strike at age 19. When I got my final strike at age 22, I was thrown away and sentenced to death in prison, otherwise known as Life Without Parole.

I own up to my mistakes, but I was also a product of my environment. I was what I had been taught. I was never given the resources or opportunities I needed to work through my trauma before I was sent away for life. At the very least, I don’t think my crime at the age of 17 should mean I should be imprisoned for my lifetime.

My life sentence is also inconsistent with both older and developing parts of Washington law; HB 1324 seeks to fix this.

The Washington State Supreme Court has repeatedly held that mandatory sentencing schemes are unconstitutionally cruel as applied to those who were under age 18 when they were accused of committing crimes ''because children are different." This is true even where children have been transferred to adult court.

The Court recognized the Constitution requires different punishments for childhood crimes because children are less mature, less able to appreciate risks and consequences, and more susceptible to negative influences. The Court concluded that a sentencing court must have full discretion and authority to consider these mitigating qualities of youth, regardless of the Sentencing Reform Act's mandatory ranges.

Like the Washington courts, our society treats children differently from adults. We take into consideration the mitigating qualities of youth. Both society and the courts consider that the brain development of children can actually prevent them from making fully formed choices in life that are beneficial for them. Their impulsivity and lack of forward-thinking prevent them from taking steps to reform and rehabilitate. These new developments in childhood brain science have been cited over and over again in numerous decisions coming out of the Washington State Appellate and Supreme Courts.

This legal reasoning is at odds with Washington’s so-called three-strikes law. The Persistent Offender Accountability Act (POAA), commonly referred to as the three-strikes law, was implemented by people’s initiative in 1994. The three-strikes law comes with an expectation that anyone who commits a strike offense will have two opportunities to reform their conduct and rehabilitate themselves. If they commit a third-strike offense, they will be sentenced to Life Without Parole–death in prison with no latitude to refrain from considering a prior strike committed as a child. The three-strikes law doesn't consider brain science, nor does it consider that people have the capacity to change.

If “children are different,” then why are we using crimes that were committed under the age of 18 as predicate strikes to sentence people to Life Without Parole under the three-strikes law? If studies on brain development have shown that children are unable to make well-informed decisions, then how can we lock up a child and expect them to rehabilitate themselves?

When we use a childhood crime for purposes of the three-strikes law, then we are saying that we expect a child to take advantage of incarceration as an opportunity for rehabilitation, something that most children in Washington's prisons and jails find difficult given the lack of resources and the amount of violence targeted at these vulnerable members of society.

The argument for continuing to use juvenile strikes is that people have had their chances, that they are violent, that they shouldn’t be in society, and that they need to be locked up for the safety of the rest of us.

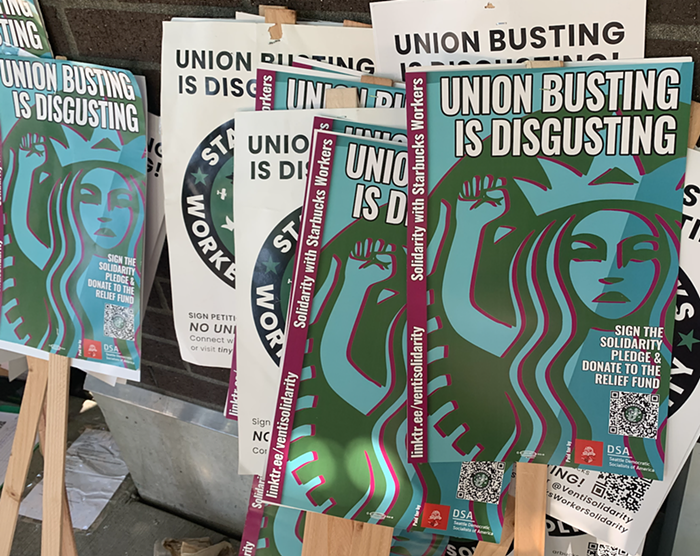

But the people we’re talking about sentencing to death in prison were once children like everybody else, many of them targeted by our state’s criminal punishment apparatus, which we know disproportionately comes for Black and Indigenous children and other children of color. And if the United States could become safer by imprisoning people, then we would be one of the safest nations in the entire world since we have the highest rate of incarceration.

All it takes to know that our prisons don’t work to end crime—even violent crime—is to look at our headlines each day. Locking people up for extremely long periods does not make us safer. Prisons in the United States do only what they were built to do, which is to allow a power structure rooted in white supremacy to control and harm Black people, Indigenous people, and poor communities while sweeping many more into the net.

What, then, gets us even a little closer to an actual system of justice? Simply put, the standard of the POAA is in conflict with emerging scientific and legal understandings and, at the very least, needs to be changed to end the use of juvenile strikes in sentencing. That’s exactly what HB 1324, a Fresh Start for Criminalized Youth, would do. Please call your legislators or submit your comment in support of HB 1324 and its companion bill, SB 5475.

Meredith Ruff, who is an attorney and organizer with No New WA Prisons, edited and contributed to this op-ed.