If you want a sterling example of life's unfairness, behold Climax Golden Twins. A brilliant, shape-shifting presence in Seattle's musical underground for nearly 30 years, the duo of Jeffery Taylor and Robert Millis couldn't land a label to release their new and best album to date, Climax Golden Twins. (Like Peter Gabriel and Caetano Veloso, CGT have issued several self-titled LPs. This one's coming out on the band's Fire Breathing Turtle imprint.) Insult to injury, they turned in the new full-length to the pressing plant a year ago—and the delays have been piling up like subpoenas in Trumpworld. At the earliest, Climax Golden Twins will manifest in physical form in December. But with the glutted state of vinyl pressing plants nowadays, who knows?

Whenever this record does hit the streets, though, it will be worth the wait. As ever with CGT, it's eclectic and cryptic. Some of the best tracks veer into territory staked out by Heliocentrics, who traffic in spacey, groove-based cuts in the vein of Europe's darkest purveyors of library music. “Rodger and the Fork,” “Erasing Richard,” and “Fifty Bucks Worth” ooze ominous, horror-film-soundtrack vibes, but with deceptively funky beats. Speaking of which, “Fervor Twins II” is a showcase for the same, plus other rhythmic twists, weird electronics, and an understatedly beautiful psychedelic guitar solo. “So Happy to See You” is cheerful, understated rock with passages of turbulence, topped by a Sonny Sharrock-ian guitar solo by Taylor.

On “Flower Hill,” a pensive, windswept acoustic-guitar folk fragility gets overtaken by a roiling, jazzy drum solo by Mark Ostrowski, then returns to its original languid beauty. “OSK” and “Evening Encounter” are successful experiments in eerie abstraction. The koto-powered “Upside Down Omen” could be a soundtrack for a scene in a surrealistic European art film in which the protagonist does something that foreshadows their fucked-up fate. The longest song, “Nebraska,” concludes the album on an aptly valedictorian, melancholy note, with Greg Kelley's poignant trumpet fanfare and Taylor's muted guitar shivers conjuring a slow-fade, sundownered ending.

Four years in the making, Climax Golden Twins features contributions from dozens of musicians, including ex-Sun City Girls members Alan and Richard Bishop, Diminished Men drummer Dave Abramson, Hound Dog Taylor's Hand drummer Ostrowski, and 310's Mary Gross. Some contributors donated recordings, some “fully formed foundations,” in Taylor's words. “Other people, we would say, 'Please send us some music, but bear in mind that we will probably be fucking with it and slicing it up and using it to our own ends,'” Taylor says in an interview at the Rendezvous, close to the first location of the Wall of Sound record store, which he co-owns.

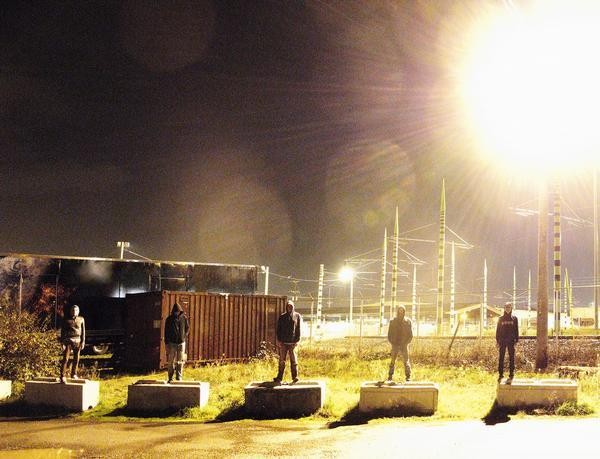

The cover of Climax Golden Twins' new album, now in pressing-plant limbo. Courtesy of Fire Breathing Turtle Records

“We also had a few overdub sessions,” Millis says. “People like Greg Kelley specifically played trumpet on some stuff. Our good friend Dave Knott came over and played ukulele on some specific tracks. It was really fun, because there were all these different approaches to each song. Whether it was built from scratch from all these bits and pieces that people had sent us or whether we had a bed to build on. In some cases, we would have a bed to build on and would more or less pull the bed out entirely—add stuff to it and get rid of the original thing. It would go in a completely different direction. We've always worked editing on the computer. We've done that together in one form or another for many years.”

Millis and Taylor spliced these discrete pieces into jam sessions that they held with Hound Dog Taylor's Hand bassist John Seman and Min Yee, former A Frames member and current Idol Ko Si bandmate with Millis. “[The album's] an interesting meeting ground of improvisation and composition,” Millis says. “We had some initial improvs, then we composed things out of them.”

Taylor says that some of the contributions are so minute that their creators may not be able to detect them. That's largely down to the post-production manipulations and editing in which CGT engage. But no matter how tiny the sound fragment, they're all equally important, says Millis.

For further inspiration for the new LP, the duo went back to their first single from 1994, which includes the forerunner to “Fervor Twins II.” They realized that their working methods basically haven't changed, but, Taylor says, they're “more polished and adept.”

“We've never done what's more typical of most musicians and bands, which is write a song and go to the studio and you realize the thing,” Millis says. “We've always used a lot of layers of improvisation. That gives us time to stretch out and mess around with ideas and have fun with it.”

“The collage aspect has always been present in our work, too,” Taylor says. “It's a result of how we started to work initially—combining sounds and thinking we need something like this to go in here and making the sound. It's always about manipulation and editing.”

“It seems like there's an overarching raison d'être for Climax Golden Twins,” Millis says, “but I don't know if there is. The Ramones, you can say, 'This is what they do.'”

“I think that happens for us, but it's in a more diffuse way,” Taylor says.

“We're both influenced by 78-rpm records,” Millis says, “but we're influenced by shorter song structures and pop music, in my case, and then yet we apply these weird electro-acoustic, musique-concrète things to shorter songs. I'm not saying that's a conscious thing, but that's just what happens.”

CGT approached the record leisurely and playfully, but the songs are rigorously constructed and their complex, deep moods make you understand why director Brad Anderson tapped them to soundtrack the 2001 film Session 9.

In some ways, Session 9 is CGT's career high point. It's their best-known and most lucrative release, despite it being an intensely brooding, minimal ambient score—the polar opposite of most sledge-hammering, Hollywood film music.

“Session 9 was a great experience, but the film came out a week before 9/11 and kind of disappeared,” Taylor says. “But for various reasons, it's become a cult classic. I think it was shown in film schools for a while because of the high-definition camera they used. That film was one of the first uses of it. But [Session 9] had some teeth and became a cult classic in the psychological-horror realm.”

Millis cackles loudly after I ask if they received more offers to do soundtrack work after the success of Session 9. “We get a lot of offers from film students and directors with no money. It's nice to feel wanted, but...” CGT did cut another soundtrack for Jennifer Lynch's 2012 movie, Chained, but the experience soured them. “The machinations of suits and how Hollywood works is not my thing,” Taylor declares. That being said, CGT will score your porn film for a reasonable sum.

Even after all of these years, CGT can't decide if they're a band or an art project. “Sometimes we've had drummers, and we have actually rehearsed songs, and even went on three or four tours,” Taylor says. “Other times it's just Jeff and I working together.

“When we started working on the new record in 2018, we had not worked together on something like this specifically—we did AFCGT [the collab with A Frames; see their great self-titled 2010 album on Sub Pop] and the Chained soundtrack—but this is the first time in a while that we've worked as Climax Golden Twins on our own record. And it was dynamite. The first day we got together to do some editing and moving things around, it was like, 'Oh, yeah! This is how we've done it forever,' and it feels really nice to be back doing it.” (For those wondering about an AFCGT reunion, it ain't gonna happen.)

CGT have every right to get discouraged by the lack of traction and sales, but they haven't. “We kind of morphed over into doing AFCGT and working on the Victrola Favorites compilations and stuff like that,” Millis says. “I started getting involved with Sublime Frequencies [as a producer of albums and films]. Jeffery was running Wall of Sound. Life gets in the way and you move on.”

Taylor has never thought of the band as a career or as a path to fame, but rather “as something that needs to be done. It's a pleasure to go play music with somebody. Whether or not there's a physical release or a record or you just play with somebody and have a nice time—that's really what it's always been about.”

Early on and to this day, people confuse or conflate CGT with Sun City Girls. Both were garnering underground attention in early-'90s Seattle, both reveled in their mysterious auras, and they were friends. “Nowadays you can't be mysterious—or you have to be consciously mysterious,” Millis says. “Back then, we didn't particularly want to look at our faces on the covers. The design aesthetic of our early records... Jeffery went to art school. I was working in art galleries. We were interested in paper texture and all this kind of stuff rather than pictures of ourselves on the cover. We've branded ourselves as being unbrandable.”

The long ordeal to get Climax Golden Twins pressed has dampened the duo's spirits, but they're excited for the public to hear it. “Different things will open up at different times upon repeated listens,” Taylor says. “I know it's a difficult thing now, because people's attention spans are like a moth, but I hope some people will really examine this record and enjoy it.”