A Stranger analysis of the criminal histories of the 113 people targeted by the City Attorney’s High Utilizer Initiative (HUI), a program designed to single-out certain “prolific offenders” for prosecution, found that nearly 65% of them have not been convicted of a crime in Seattle Municipal Court (SMC) since January 1, 2020.

That’s probably because more than half of them are Trueblood class members. Members of the Trueblood class have a history of mental illness that has rendered them incompetent to stand trial, and they are therefore ineligible for misdemeanor prosecution.

Meanwhile, just 20 people on the list account for half of the Seattle Municipal Court convictions I logged from HUI list members in the last five years. Of those 20, half are homeless.

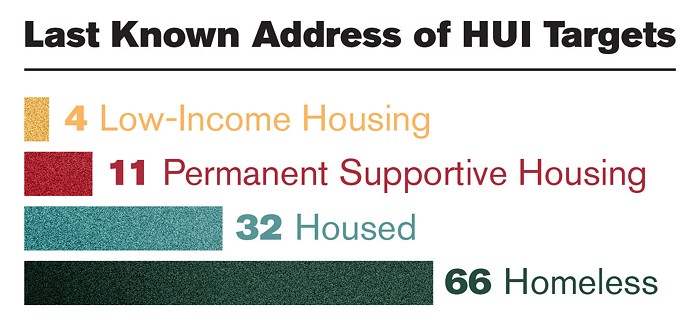

That proportion basically holds true for the list as a whole. The Stranger's analysis found that court records listed a homeless shelter or other precarious housing as the last known address for 58% of the 113 people on the list. (Cops listed a church as the last known address for two of those people, and a motel for another person. They also listed "1234 Homeless St" as one person's address, a joke I'm sure the cop found hilarious.) As for the rest, 28% listed a house or an apartment, 10% listed permanent supportive housing, and 3.5% listed low-income housing.

Seattle’s HUI program also replicates the racial disparities of the criminal legal system: 28% of the people on the list are Black, while only 7% of Seattle’s population identifies as Black, according to the latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The City Attorney’s Office (CAO) launched the initiative in March to “identify individuals responsible for repeat criminal activity across the City of Seattle” and “dramatically reduce their public safety impacts.” But trying to prosecute and jail a bunch of people who are ineligible for prosecution anyway only runs a disproportionately high number of mentally ill people and Black people through a wringer that has “no effect on reoffending or slightly increases it,” according to a meta-analysis of 116 studies.

The HUI List Perpetuates the Criminal Legal System’s Racial Disparities

The percentage of Black people on the HUI list (28%) nearly equals the percentage of people the Seattle Police Department arrests who identify as Black (29.4%). That makes sense, because the program stems from the CAO’s choice to use referrals from SPD as its sole criteria for adding people to the CAO’s naughty list. Those on the list have 12 or more referrals in the last five years, including at least one in the last eight months.

An important note: “referrals” do not necessarily indicate guilt. A “referral” just means that someone saw a person behaving in a way they viewed as disorderly, and then decided to call the cops, who resolved the caller’s complaint by arresting the disorderly person or issuing that person a citation. In some cases, the disorderly person may have left the scene before the cops arrived, but the cops made a referral for prosecution anyway based on a positive ID from the caller or other witnesses. Though the person referred for prosecution may have actually committed the crime in question, such as shoplifting or trespassing, our legal system presumes innocence until proven guilty.

The Seattle Police Department remains the subject of federal oversight due to its history of racially biased policing, so the fact that the cops refer Black people for prosecution at disproportionately high rates relative to their population shouldn’t surprise anyone, including the City Attorney’s Office.

And in fact, it doesn’t. But they’re choosing to reinforce those disparities through this HUI program anyway. In an email, a spokesperson for the CAO shifted blame for the disparities on their list from the law department to the overall over-representation of people of color in the criminal legal system “here in Seattle, and in most major cities across the U.S.”

Prosecutions Do More Harm Than Good for Many People on the HUI List

Anita Khandelwal, director of King County’s Department of Public Defense, has expressed doubts about the HUI program’s effectiveness from its inception. Now that she’s seen the initiative in action, she believes the CAO should scrap it entirely.

In a statement, she said the DPD urges the City Attorney to “put aside this list and to instead support community efforts that will address real needs and solve real problems.” In her view, “[p]eople who are suffering need support and resources, not prosecution and incarceration.”

Facing prosecution remains “one of the biggest barriers” to addressing the problematic behavior that leads cops to refer people for prosecution in the first place, said Tiarra Dearbone, who has worked with people on the HUI list in her capacity as program director for an arrest diversion program called LEAD.

Even if judges quickly dismiss cases after discovering that defendants count as members of the Trueblood class, for instance, the process of showing up in court and confronting a prosecutor can traumatize people and disrupt their progress in treating their mental illness, she added.

How the High Utilizer Initiative Operates in Practice

Prosecution is not the only tool in the criminal legal system’s belt. Judge Damon Shadid oversees the Seattle Municipal Court’s attempt to connect low-level offenders to services instead of jail through a program called Community Court. Like Khandelwal and Dearbone, he also believes that focusing on mainstream prosecutions for most people on the HUI list is counterproductive.

In a phone interview, he agreed with Khandelwal’s preference for prioritizing services, such as permanent supportive housing and welfare programs that provide a legal means of income, which will address the behavioral or economic drivers of this disruptive behavior. “What these people need most is permanent supportive housing,” he said. “The jail is not an alternative to permanent supportive housing, period.”

He went on to say that the people who have been trying to help the people on the HUI list for years didn’t need a new program from the City Attorney to know who needs the most help and who has been causing the most disruptions in the city. As I ticked off several names of people whose criminal histories had incomplete or confusingly coded information to confirm that I hadn’t missed something in their records, Shadid sighed at the mention of each name in turn.

He rattled off a history of the various interventions the legal system had tried to use in each person’s case without needing to see the person’s records, proving his point in depressing detail. Shadid told me he remains hopeful that the City Attorney’s Office will shift its focus to more service-oriented individual plans for the people on the HUI list as the department realizes through experience that most of the tools available to prosecutors haven’t worked and aren’t likely to help anytime soon.

The City Attorney’s Office denies that their goal is to arrest and incarcerate every person on the HUI list. And, to their credit, they’ve consistently indicated that they care about connecting these people to those supportive services. But their actions don’t match their messaging.

As I’ve previously reported, several people on the list are currently facing prosecution solely because their inclusion on the HUI list bars them from less-punitive diversion programs, such as Community Court.

If those cases on which I reported were outliers, and if the City Attorney’s Office was actually using its bench attorneys as case managers to work closely with service providers to connect people on the list with housing and services, then the CAO would be working to achieve its righteous goal. But, according to Tiarra Dearbone from LEAD, that’s not really happening in a systematic fashion. LEAD does have a dedicated prosecutorial liaison within the City Attorney’s Office, but that role existed prior to the HUI program, and it doesn’t give people on the list any special access to services.

Since the City Attorney’s Office started training SPD officers on the list at roll call meetings in late April, Dearbone told me they’ve only received two referrals for people on the list: one from law enforcement, and one from the CAO. There are 113 people on the latest version of the list, and I’ve already written about three of them facing prosecution since May.

If the CAO was actually serious about prioritizing services over arrest and incarceration, then the number of prosecutions I’ve reported on wouldn’t exceed the number of cases sent to the City's premier diversion program.

So, How Can the City Attorney’s Office Solve this Problem?

If they’re determined to ignore Khandelwal’s suggestion to scrap the list entirely, there are other ways the CAO could still use the HUI program to do the things it says it wants to do. For starters, the CAO could remove from the list anyone who hasn’t been convicted of a misdemeanor for a certain time, which would incidentally save taxpayers a bunch of money on prosecutions against Trueblood class members that will be dismissed almost immediately anyway.

As for the rest of the people they’re singling out for prosecution, again, the evidence shows that jailing doesn’t really work that well and may even increase the likelihood of people re-offending. And jail is all they’re getting. As I’ve previously reported, these prosecutions do not give people on the HUI list any special access to services they couldn’t otherwise receive outside of the system.

On a systemic level, the City Attorney’s Office could use its influence within Seattle’s public safety debate to make the case that the city, the state, and the federal government needs to spend more money to build more supportive housing and to expand behavioral health services now.

Those investments would take time to change the daily conditions on Seattle’s streets, but they would also make clear for the public that the people who should be “held accountable” for our public safety crisis are the politicians at every level of government who have repeatedly defunded our social safety net since the Reagan administration.

In the near term, Dearbone told me that LEAD has been advocating for City leaders to prioritize the limited supply of permanent supportive housing for its clients. While LEAD doesn’t currently have enough employees to manage everyone on the HUI list, she said that prioritizing the limited resources the City does have for the people creating a disproportionate impact on public safety would actually help those people get what they need to change their disruptive behavior.

Dearbone also said that LEAD has invited the CAO to join them in that advocacy, but that no one from the City Attorney’s Office has participated in those meetings. She also confirmed that LEAD does not currently have a meeting on the books with the CAO to plan any coordinated advocacy in the future.