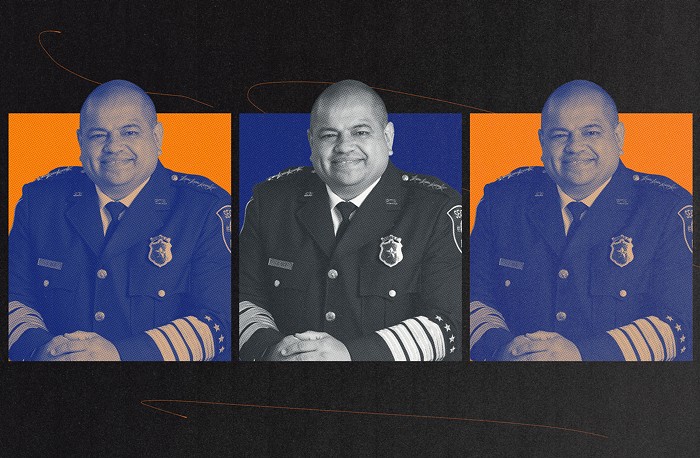

In a letter to Mayor Jenny Durkan and Council President Lorena Gonzalez, interim Seattle Police chief Adrian Diaz said he declined the Office of Police Accountability recommendation to discipline the East Precinct commander who ordered cops to launch tear gas and blast balls at a largely peaceful crowd after a tussle over a pink umbrella.

That "pink umbrella" incident established 11th and Pine as the primary protest zone in Seattle last summer, and transformed the anger about racist police brutality in the US more broadly into anger about the Seattle Police Department's racist brutality in particular, a grievance that carries on to this day both in the streets and in City Hall.

If you don't remember what that moment looked like, then allow the Wall Street Journal to break it down for you:

In the letter, Diaz argued that superiors ultimately made the decision to gas the neighborhood, and that punishing the commander for the "decisions of others at higher levels of command" would breach the "principles of fairness" that guide his personal moral compass.

The interim chief's near-criminal use of the passive voice throughout the letter allowed him to avoid naming the person or persons who made the decision. And rather than suggest discipline for those higher-ups, Diaz basically said the department changed some of its tactics and restructured its command process to clear up accountability ambiguities, so everything's fine now.

Over the phone, Council President Lorena Gonzalez said, “I think there’s no question that the evidence shows that this named employee was behaving in a way that was out of policy, and that means that officer needs to be held accountable.”

This outcome, she added, “is going to be top of mind for me as I continue to be asked to make decisions about bargaining with the police guild and how to make sure that our contract is not going to further erode the power and authority of our OPA director…. If that means reopening our 2017 police accountability ordinance to clean this up and make sure that decisions to overturn these civilian oversight findings are being done more appropriately, then that’s something that’s top of mind.”

In a statement, Seattle City Councilmember and public safety chair Lisa Herbold noted that the OPA report mentions no other commander giving orders and asks two important questions: "If Chief Diaz is basing his reversal of the OPA on the theory that the named employee was following the orders of a superior, I ask why this was not reflected in the investigation and that the Chief tell us how these others higher in the chain of command, whose actions in this matter of which he is apparently aware, will be held accountable for a misuse of force & unwarranted dispersal order."

In lieu of holding my breath while waiting for SPD to answer, I'll focus my brief tirade on the two weak-ass justifications Diaz used to buttress his decision. "There are two realities concerning the events of this summer that I cannot sidestep here," he wrote. One "reality" was "the complexity of incident command in such circumstances," and the other was the "unprecedented" nature of the protests.

To highlight his certainty that SPD had never handled such large protests before, Diaz used the word "unprecedented" three times throughout the letter. Allow me to run through them quickly, emphasis mine: "The events of this past summer, occurring in the midst of a deadly pandemic where staffing and communications were already challenged, were unprecedented in their scope, duration, and in some instances, violence and intensity," he wrote. And then later, "...cannot lose sight of the abjectly unprecedented and rapidly dynamic circumstances at hand." And then later, "...in the midst of the unprecedented circumstances at hand."

Setting aside his misuse of the word "abjectly," the idea that last summer's demonstrations were "unprecedented" is simply ahistorical in a town known partly for its protest of the World Trade Organization in 1999, when SPD also gassed largely peaceful crowds downtown and on Capitol Hill. (Cops also rehearse this little ritual every year on May Day, when they throw blast balls at a bunch of twentysomething anarchists who dress up in black and bust up a Nike store, but I digress.)

As the Seattle City Council's 2000 Accountability Review Committee (ARC) report shows, back in 1999 the SPD faced a very similar version of the situation they encountered on Capitol Hill on June 1, 2020.

The report's section on "The Events on Capitol Hill," which lasted for "two chaotic nights" in late fall, remain particularly instructive. Stop me if any of this sounds familiar.

"Under-staffed and often exhausted police made questionable strategic and tactical judgments, which created serious questions for the committee about the protection of civil rights. The unintended consequence of police actions on Capitol Hill was to bring sleepy residents out of their homes and mobilize them as 'resistors,'" the committee wrote.

Back then the trouble all began when SPD pursued a crowd from downtown up to Capitol Hill, "allegedly based on the conviction of a field commander that protestors should not be allowed to hold 'high ground' from which police could be pelted with rocks or bottles (reports differ about the seriousness of this threat)." The result of that action? "Protestors found supporters among Capitol Hill residents and bystanders galvanized by police action."

Police went over the top, the report goes on to say, when they became "understandably worried that there would be an assault on the East Precinct Station at 12th and Pine, as it had previously been the target of attacks and vandalism" and then attempted to "'rescue' stranded officers" reportedly caught up in the crowd.

"ARC investigators found the rumors of 'Molotov cocktails' and sale of flammables from a supermarket had no basis in fact. But, rumors were important in contributing to the police sense of being besieged and in considerable danger," according to the report, emphasis mine.

After looking at all the details of that protest, investigators concluded "it may have been wiser just to let citizens stand in the rain rather than force dispersal with gas and other means." After offering that conclusion, the council members recommended that the department articulate a crowd management policy "after dialogue with the community that spells out expectations of all involved."

The cops apparently did develop a crowd management policy, and that policy, as the OPA report of the pink umbrella incident laid out, said that "when feasible, a dispersal order should be given and the crowd afforded sufficient time to disperse prior to the use of blast balls and OC." Moreover, those chemical weapons should "not be deployed in the vicinity of people who do not pose a threat to safety or property, and that the "[incident commander] retains ultimate responsibility for the decisions of subordinates."

The commander failed to follow those policies, and so he should face discipline. As should the higher-ups. But he won't—and not because of the "unprecedented" nature of the protest, or because of some obscure principle of fairness within a command structure, but because holding a commander accountable internally for the police violence on that day would violate the Thin Blue Line tribalism that permeates SPD's culture.

As the Seattle Community Police Commission said in a statement yesterday evening, "There have been tens of thousands of complaints against SPD over the past year, but only a handful of investigations have met the high bar OPA has set to find police officers have committed misconduct. This case met that high bar. Chief Diaz's decision to overturn OPA's decision is detrimental to community trust in SPD and Seattle's entire police accountability system."

In a statement, SPD said "the investigation into who is ultimately responsible continues" and that "Chief Diaz is committed to holding the right person accountable." So someone may be held responsible after all if they can ever get to the bottom of this mystery.